Have you ever watched a bird soaring through the sky or hopping along a branch and wondered how its body works? Birds are fascinating creatures with unique adaptations that allow them to fly, swim, and thrive in diverse environments. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the various body parts of birds, helping beginners understand the intricacies of avian anatomy. So, let’s spread our wings and dive into the world of bird body parts!

Table of Contents

Introduction to Bird Anatomy

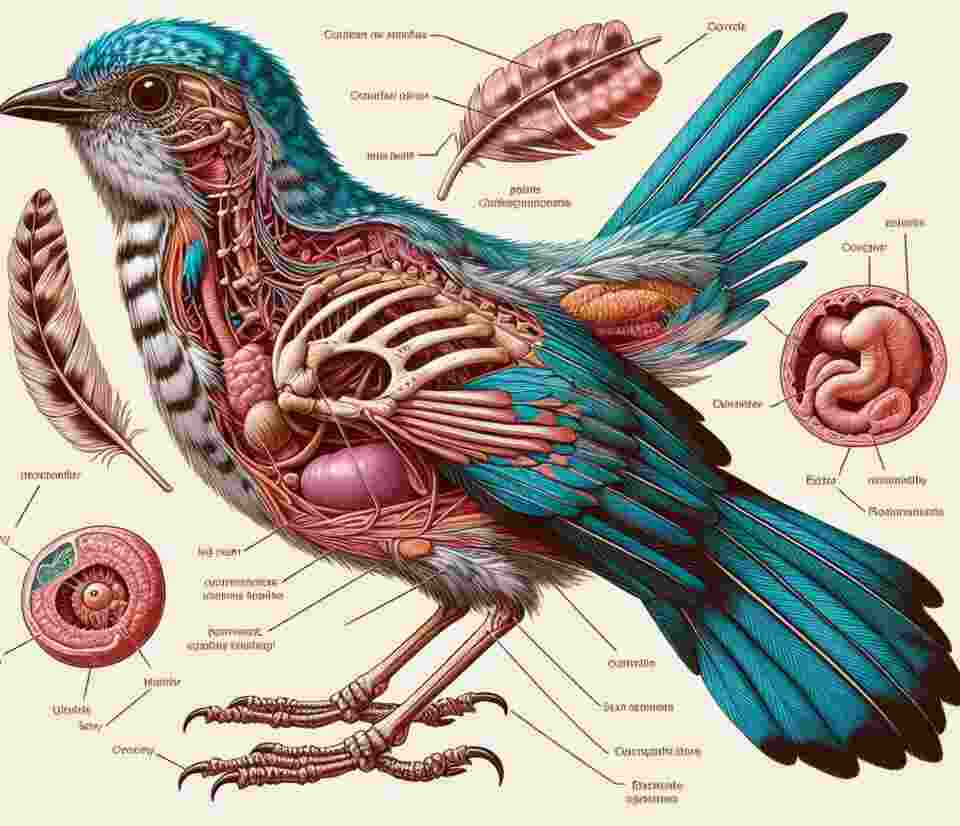

Birds are a diverse group of animals, with over 11,000 known species inhabiting nearly every corner of the globe. Despite this diversity, all birds share a common anatomical structure that sets them apart from other vertebrates. Their bodies are specially adapted for flight, with lightweight bones, powerful muscles, and streamlined shapes.

Understanding bird anatomy is crucial for anyone interested in ornithology, birdwatching, or simply appreciating the natural world around us. By learning about the different body parts of birds, we can better comprehend their behavior, diet, habitat preferences, and evolutionary history.

External Body Parts

Let’s start our exploration with the parts of a bird that we can easily observe from the outside.

Feathers

Feathers are perhaps the most distinguishing feature of birds. These lightweight, complex structures serve multiple purposes:

- Flight: Primary and secondary flight feathers on the wings provide lift and maneuverability.

- Insulation: Down feathers trap air close to the body, keeping birds warm.

- Waterproofing: Contour feathers have interlocking barbules that create a water-resistant surface.

- Display: Colorful or elaborate feathers play a role in courtship and species recognition.

Feathers come in various types, each with a specific function:

| Feather Type | Location | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Contour | Outer body | Streamlining, waterproofing |

| Flight | Wings, tail | Propulsion, steering |

| Down | Close to skin | Insulation |

| Semiplume | Under contour | Additional insulation |

| Filoplume | Throughout body | Sensory perception |

| Bristle | Around eyes, mouth | Protection, sensory |

Birds regularly preen their feathers to keep them clean and in good condition, using their beaks to distribute oil from a gland near the tail.

Beak

The beak, also known as the bill, is a bird’s most versatile tool. It’s made of keratin, the same protein found in human fingernails, and grows continuously throughout a bird’s life. Beaks come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, each adapted to the bird’s diet and lifestyle:

- Hooked beaks: Found in raptors like eagles and owls, perfect for tearing meat.

- Conical beaks: Common in seed-eating birds like finches, ideal for cracking open seeds.

- Long, thin beaks: Seen in hummingbirds and sunbirds, adapted for sipping nectar from flowers.

- Spatulate beaks: Used by spoonbills and pelicans for scooping fish from water.

Birds use their beaks for feeding, preening, nest-building, defense, and even courtship displays.

Eyes

Birds have large eyes relative to their body size, with excellent color vision that often extends into the ultraviolet spectrum. Unlike humans, most birds have eyes on the sides of their heads, providing a wide field of view that helps them spot predators and prey.

Key features of bird eyes include:

- Nictitating membrane: A translucent third eyelid that protects the eye while still allowing some vision.

- Oil droplets: Colored filters in the retina that enhance color perception and reduce glare.

- Tetrachromatic vision: The ability to see four primary colors, compared to humans’ trichromatic vision.

Some birds of prey, like owls, have forward-facing eyes that provide binocular vision, crucial for judging distances when hunting.

Wings

Wings are the defining characteristic that allows most birds to fly. They are modified forelimbs, analogous to human arms, but specially adapted for flight. The main components of a bird’s wing are:

- Humerus: The upper arm bone.

- Radius and ulna: The forearm bones.

- Carpometacarpus: Fused wrist and hand bones.

- Alula: A small, thumb-like structure that helps with slow-speed maneuverability.

- Primary feathers: The long, outer flight feathers attached to the hand bones.

- Secondary feathers: Shorter flight feathers attached to the ulna.

- Coverts: Smaller feathers that overlay the base of the flight feathers, improving aerodynamics.

The shape and size of wings vary greatly depending on the bird’s lifestyle:

- Long, narrow wings (e.g., albatrosses): Excellent for soaring over long distances.

- Short, rounded wings (e.g., quails): Good for quick takeoffs and maneuverability in dense vegetation.

- Pointed wings (e.g., swifts): Ideal for fast, agile flight.

Tail

The tail serves as a crucial flight control surface, acting like a rudder to help birds steer and balance. It consists of long feathers called rectrices, which can be spread or folded to adjust air resistance and direction.

Tails come in various shapes, each with its own advantages:

- Fan-shaped: Provides good maneuverability (e.g., woodpeckers).

- Forked: Enhances agility in flight (e.g., swallows).

- Long and tapered: Helps with balance and steering (e.g., magpies).

- Short and square: Offers stability (e.g., ducks).

In addition to its role in flight, the tail is often used in courtship displays and can serve as a prop for climbing (as in woodpeckers) or a counterbalance when perching.

Legs and Feet

Bird legs and feet are remarkably diverse, adapted to a wide range of habitats and lifestyles. The basic structure includes:

- Femur: The thigh bone, often hidden by feathers.

- Tibiotarsus: The shin bone, fused with part of the ankle.

- Tarsometatarsus: A fusion of ankle and foot bones, often erroneously called the “leg.”

- Toes: Usually four (though some birds have fewer), with various arrangements.

The most common toe arrangement is anisodactyl, with three toes pointing forward and one backward. However, other arrangements exist:

| Toe Arrangement | Description | Example Birds |

|---|---|---|

| Zygodactyl | Two toes forward, two back | Parrots, Woodpeckers |

| Heterodactyl | Two outer toes back, two inner forward | Trogons |

| Syndactyl | Three front toes partially fused | Kingfishers |

| Pamprodactyl | All four toes pointing forward | Swifts |

Feet are adapted to various functions:

- Perching: With long, curved toes for gripping branches.

- Swimming: With webbed toes for efficient paddling.

- Wading: With long legs and spread-out toes to distribute weight on soft surfaces.

- Grasping: With sharp talons for catching and holding prey.

Internal Body Parts

While not visible from the outside, the internal anatomy of birds is just as fascinating and specialized as their external features.

Skeletal System

The avian skeleton is a marvel of evolutionary engineering, optimized for flight while still providing strength and support. Key features include:

- Pneumatic bones: Many bones are hollow and filled with air sacs, reducing weight without sacrificing strength.

- Fused bones: Several bones, like those in the skull and pelvis, are fused to provide rigidity.

- Keeled sternum: A large breastbone that anchors powerful flight muscles.

- Flexible neck: Birds typically have more cervical vertebrae than mammals, allowing for greater head mobility.

- Pygostyle: A fused set of tail vertebrae that supports tail feathers.

The skeleton of a bird typically makes up only about 5% of its total body weight, compared to around 15% in mammals of similar size.

Respiratory System

Birds have the most efficient respiratory system of any vertebrate, a necessity for the high energy demands of flight. The system includes:

- Lungs: Compact and relatively rigid, unlike the expandable lungs of mammals.

- Air sacs: Thin-walled structures that extend into the body cavity and even some bones, acting as bellows to move air through the lungs.

- Parabronchi: Tiny air capillaries in the lungs where gas exchange occurs.

This system allows for continuous, one-way airflow through the lungs, maximizing oxygen uptake. Birds can extract up to twice as much oxygen from the air they breathe compared to mammals.

Digestive System

The avian digestive system is adapted for quick processing of food and efficient extraction of nutrients, necessary for their high metabolism. Key components include:

- Crop: A pouch in the esophagus used for food storage.

- Proventriculus: The first, glandular part of the stomach that secretes digestive enzymes.

- Gizzard: A muscular second stomach that grinds food, often with the help of swallowed stones (grit).

- Intestines: Relatively short compared to mammals, as birds need to stay lightweight for flight.

- Cloaca: A common opening for the digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts.

Birds lack teeth, using their beaks to manipulate food instead. Many species swallow their food whole, relying on the gizzard to break it down.

Circulatory System

The avian heart is proportionally larger and more powerful than that of comparably sized mammals, necessary to meet the high oxygen demands of flight. It has four chambers (like mammals) but is more efficient:

- Larger left ventricle for pumping oxygenated blood to the body.

- Complete separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood.

- Higher heart rates, often exceeding 500 beats per minute during flight.

Birds also have a higher body temperature than mammals, typically around 40°C (104°F), which helps maintain the high metabolic rate needed for flight.

Reproductive System

Most male birds lack external genitalia, with both males and females having internal reproductive organs that connect to the cloaca. Key features include:

- Testes (males): Typically enlarge during breeding season.

- Ovaries (females): Usually only the left ovary is functional to reduce weight.

- Oviduct: Where eggs are formed and fertilized in females.

Unlike mammals, female birds produce eggs with large yolks, providing nutrition for the developing embryo outside the body.

Specialized Adaptations

Many birds have developed unique adaptations to suit their particular lifestyles:

- Woodpeckers: Reinforced skulls, long tongues that wrap around the brain for shock absorption, and stiff tail feathers for support while climbing.

- Hummingbirds: Ability to hover and fly backwards, extremely fast wing beats (up to 80 times per second).

- Penguins: Wings modified into flippers for “flying” underwater, dense bones for diving, and specialized feathers for insulation in cold water.

- Flamingos: Long legs and necks for feeding in shallow water, specialized beaks with lamellae for filter feeding.

These adaptations showcase the incredible diversity and specialization within the bird world.

Comparing Bird Anatomy to Other Animals

While birds share some basic anatomical features with other vertebrates, they have many unique characteristics:

- Feathers: No other animal group has true feathers.

- Air sacs: This respiratory feature is unique to birds and some reptiles.

- Hollow bones: While some other animals have hollow bones, the extent in birds is unparalleled.

- Beak: While some other animals have beak-like structures, the true keratin beak is a bird feature.

- Egg structure: Bird eggs have a hard calcium carbonate shell, unlike the leathery eggs of most reptiles.

These differences highlight the specialized nature of bird anatomy, driven by the demands of flight and their unique evolutionary history.

Conclusion

From their lightweight bones to their powerful hearts, from their keen eyes to their versatile beaks, birds are marvels of natural engineering. Each body part we’ve explored plays a crucial role in allowing these remarkable creatures to thrive in diverse environments across the globe.

Understanding bird anatomy not only enhances our appreciation of these feathered wonders but also provides insights into their behavior, ecology, and evolution. Whether you’re a budding birdwatcher, a student of biology, or simply someone who enjoys the natural world, knowing about bird body parts opens up a new dimension of observation and appreciation.

As you continue your journey into the world of birds, remember that each species has its own unique adaptations and variations on these basic anatomical themes. The next time you see a bird, take a moment to observe its various body parts and consider how they all work together in perfect harmony, allowing the bird to fly, feed, and flourish in its own special niche in the world.

Happy birding, and may your newfound knowledge of bird anatomy enrich your encounters with our feathered friends!