When temperatures plunge below freezing and snow blankets the landscape, it’s astonishing to see how birds survive winter. Tiny birds weighing less than an ounce maintain body temperatures around 105°F even when the air drops to -40°F or colder. Species like black-capped chickadees, northern cardinals, and dark-eyed juncos not only survive but stay active through winter’s harshest conditions.

According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, small birds like redpolls weighing less than 15 grams can survive temperatures that plunge nearly 100 degrees below freezing. How do they accomplish this seemingly impossible feat? This comprehensive guide synthesizes findings from ornithological research, physiological studies, and field observations to explain the remarkable adaptations that allow birds to endure winter. 😮

- Small birds maintain body temps ~105°F even in subzero weather.

- Feathers insulate; fluffing creates air pockets to trap heat.

- Countercurrent heat exchange keeps legs/feet from freezing.

- Torpor lowers body temperature and metabolism to save energy overnight.

- Food caching and mixed-species foraging support energy needs.

- Roosting in cavities, snow burrows, or dense evergreens provides warmth.

- High-fat diets, supplemental feeders, and water are critical for survival.

Combine shelter, food, and observation to help winter-resident birds thrive safely.

Table of Contents

- 1 Watch How Birds Brave Winter

- 2 Why Winter Is Challenging for Birds

- 3 The Migration Alternative: Why Some Birds Leave

- 4 Feather Insulation: Nature’s Best Cold-Weather Technology

- 5 Countercurrent Heat Exchange: Keeping Feet Warm

- 6 Torpor: Strategic Hypothermia for Energy Conservation

- 7 Food Caching: Memory as a Survival Tool

- 8 Roosting Behavior: Communal Warmth and Shelter

- 9 Shivering and Metabolic Heat Production

- 10 Winter Diet and Feeding Strategies

- 11 Helping Birds Survive Winter: Research-Based Recommendations

- 12 Species-Specific Winter Survival Strategies

- 13 Winter Mortality: What the Research Shows

- 14 Common Questions About Birds in Winter

- 15 Winter Survival at a Glance

- 16 Conclusion: Remarkable Resilience Through Evolution

- 17 Author

Watch How Birds Brave Winter

See these incredible cold-weather adaptations in action with this quick, visual explainer.

Show Transcript:

0:00

Have you ever looked out your window on a freezing winter day and noticed a tiny bird, all fluffed up, and wondered, how on earth do they survive? These small, seemingly fragile birds face some of the harshest conditions nature can throw at them. Today, we’re uncovering the secrets behind how birds survive winter and thrive against the odds.

0:23

This is the ultimate puzzle: small birds must maintain a core temperature nearly 150°F warmer than the freezing air around them. Imagine being a tiny flying furnace, working nonstop to stay warm.

0:49

Keeping that furnace roaring requires enormous energy. To survive, a small bird’s daily calorie needs are equivalent to a human eating roughly 67,000 calories—or 27 large pizzas every day—while finding food buried under snow and ice.

1:31

So, how do they manage? The first secret lies in their gear. Birds wear some of the most advanced natural winter clothing: feathers.

1:41

They have a two-layer system: a tough, waterproof outer layer acting like a windbreaker, and a soft downy layer underneath that traps warm air next to the skin. During winter, many birds grow up to 30% more insulating feathers, and that puffed-up look? Not fat—it’s a clever strategy to trap extra heat and reduce heat loss by a third.

2:08

But feathers aren’t the whole story. Their legs and feet remain bare, often touching ice or metal. Logic says they should freeze—but they don’t. Why? Birds use a remarkable biological system called countercurrent heat exchange.

2:39

Here’s how it works: warm blood flows from the body through arteries wrapped around veins returning cold blood. Heat naturally transfers from warm to cold blood, pre-warming it before it returns to the body. This lets their feet stay just above freezing without wasting energy.

3:15

Even with insulation and heat recycling, the long winter night is a test. Birds survive through a state called torpor, a mini-hibernation where their body temperature drops 20°F, slowing metabolism and saving massive energy. Torpor can increase a small bird’s winter survival chance by up to 58%, even if it makes them sluggish at dawn.

4:08

Physical adaptations are amazing, but survival also depends on intelligence and strategy. Birds that stay through winter plan months in advance. Chickadees, for example, hide up to 80,000 seeds in thousands of locations across their territory and remember every single one. Their hippocampus grows each fall—essentially a GPS upgrade for winter survival.

5:01

Birds also use clever behaviors: huddling for warmth, sheltering in tree cavities that can be 10°F warmer than open air, and some species, like grouse, even burrow into snowbanks for insulation.

5:31

We can help too. High-calorie foods are critical. Black oil sunflower seeds are perfect for most birds, and suet acts as a pure energy bar for species like woodpeckers and chickadees. Water is equally important; clean, thawed water is vital for drinking and keeping feathers in top insulating condition. Heated bird baths can literally save lives.

6:16

Providing shelter is another way to help. Even a simple brush pile or planting dense evergreens can give birds protection from wind and predators. Roosting boxes allow groups of birds to huddle together on the coldest nights.

6:36

The next time you see a tiny chickadee at your feeder, remember: this isn’t just a casual visitor. You’re watching an elite survivalist at the peak of its ability. Every feather, physiological adaptation, and memory system is honed over millions of years to endure harsh winter conditions.

7:01

Every winter day is a battle for life. Now that you know their secrets, incredible resilience, and survival adaptations, the only question is: how will you help play a role in their story?

Why Winter Is Challenging for Birds

Winter presents three fundamental survival challenges that push birds to their physiological limits:

Challenge 1: Extreme Cold As warm-blooded (endothermic) animals, birds must maintain high body temperatures within a narrow range, typically 104-108°F depending on species. The colder their environment, the more body heat they lose. According to research on adaptive energy management in small wintering birds, these species must greatly increase energy intake and modify body mass and metabolic rates to survive cold conditions and limited foraging time.

Challenge 2: Food Scarcity Counteracting heat loss requires ramped-up metabolism, which demands extra food precisely when food becomes scarce. Insects disappear, plants cease producing, and snow buries seeds and berries. Birds need to consume frequent food throughout winter to fuel heat production and stay active, especially as food becomes scarcer and energy demands increase, according to the Cornell Lab’s How Do Birds Survive the Winter guide.

Challenge 3: Short Days Winter’s abbreviated daylight provides limited foraging time. Birds must find enough food in 8-10 hours to fuel metabolism for 14-16 hour nights. This compressed feeding window intensifies the energy challenge dramatically.

A landmark 1966 Finland winter bird survival study documented these challenges clearly. During an exceptionally cold winter, researchers from the University of Helsinki conducted a countrywide bird survey, as summarized in how birds survive in winter. Small resident insectivores suffered the highest mortality; Eurasian Treecreepers, Long-tailed Tits, and Goldcrests all experienced heavy losses. Birds that couldn’t migrate south and couldn’t switch to seed-based diets faced the harshest conditions.

The Migration Alternative: Why Some Birds Leave

Approximately two-thirds of North American bird species migrate south each year, avoiding winter’s challenges entirely. Migration represents a proven survival strategy, though not without its own risks, predation during travel, exhausting energy expenditure, and navigating thousands of miles twice annually.

Facultative migration describes species that migrate only when conditions become particularly harsh. European Goldfinches and Bohemian Waxwings in the Finland study exemplified this strategy, moving south only during the severe winter but remaining in milder years.

Why some birds stay: Species like chickadees, cardinals, blue jays, nuthatches, titmice, and juncos possess specialized adaptations making staying put energetically favorable compared to migration’s costs. These cold-hardy species have evolved remarkable physiological and behavioral strategies for surviving northern winters.

Feather Insulation: Nature’s Best Cold-Weather Technology

Bird feathers provide insulation rivaling the best human-engineered winter clothing. The secret lies in their complex structure and air-trapping capabilities.

How feather insulation works: According to Audubon research, bird feathers repel water while a base layer of fine, downy feathers traps body heat against the skin while keeping frigid air out. This two-layer system, outer waterproof barrier plus inner insulation, creates exceptional thermal protection.

Seasonal feather changes: Birds in colder climates often grow heavier plumage for winter. Some species add 25-30% more feathers compared to summer plumage. This increased feather mass improves insulation without significantly impacting flight capability.

Fluffing behavior: A puffed-up cardinal or chickadee in winter isn’t gaining weight, it’s maximizing insulation. When birds fluff up, they create hundreds of tiny air pockets between feathers that trap warm air close to the body. This behavior can reduce heat loss by 30% or more according to thermoregulation studies.

Feather maintenance is critical: The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service notes that keeping feathers clean, dry, and flexible is essential for maintaining insulating layers, as explained in how birds keep warm in winter. Birds spend significant time preening, applying oil from their uropygial gland to waterproof feathers and ensure they maintain proper structure.

Countercurrent Heat Exchange: Keeping Feet Warm

One of winter’s most fascinating adaptations involves how birds keep their unfeathered legs and feet functional without losing excessive body heat.

The problem: Bird feet and legs lack feathers, they’re mainly bones and tendons with minimal muscle. Exposed to freezing air, these appendages should become ice-cold blocks within minutes, yet birds perch comfortably on frozen branches for hours.

The solution – Regional Heterothermy: According to research documented by Audubon Vermont, birds employ countercurrent heat exchange in their legs. Warm arterial blood flowing from the body toward the feet runs directly alongside veins carrying cooled blood returning from the feet. Heat transfers laterally between these adjacent blood vessels, pre-warming returning blood and pre-cooling outbound blood.

The remarkable result: Chickadee feet can cool to near-freezing temperatures (around 30°F) while body core remains at 105°F. Cornell research confirms birds don’t “feel cold” the way humans would, they’re not uncomfortable until tissue damage from ice crystal formation begins.

Why this matters: If birds maintained feet at body temperature, they’d lose heat so rapidly that they couldn’t eat fast enough to compensate. Energy depletion would occur quickly, likely proving fatal. By allowing feet to cool near ambient temperature, birds dramatically reduce heat loss while maintaining enough warmth to prevent freezing damage.

Additional adaptations: According to Audubon, waterfowl and other species further conserve heat by standing on one leg or sitting down, tucking one leg into belly feathers for warmth while balancing on the other. They also tuck bills under back feathers, keeping these bare parts warm while utilizing warmer exhaled air for breathing efficiency.

Torpor: Strategic Hypothermia for Energy Conservation

Perhaps the most remarkable winter survival adaptation is torpor, a controlled reduction in body temperature and metabolic rate that dramatically reduces energy expenditure.

What is torpor? Torpor involves voluntarily lowering body temperature from the normal 105°F down to 80-90°F or even lower in some species. Metabolic rate drops proportionally, sometimes by 50% or more. This hypometabolic state conserves precious energy during the longest, coldest nights.

Research published in Oecologia used stochastic dynamic programming models to evaluate torpor’s survival benefit. The findings were striking: nocturnal hypothermia increased winter survival for small northern birds by 58% over a 100-day winter period compared to maintaining normal body temperature throughout.

How deep can birds go? Depth varies by species and conditions:

- Mild hypothermia: Body temperature drops 3-5°C below normal

- Deep hypothermia/torpor: Body temperature drops 5-10°C or more

- Extreme cases: Some hummingbirds can drop body temperature to near 40°F during torpor

The chickadee example: Black-capped chickadees may decrease body temperature from 107°F down to 86-90°F during cold nights. According to Vermont Audubon research, chickadees’ enlarged hippocampus (brain region responsible for spatial memory) grows even larger in fall, helping them remember thousands of cached food locations that sustain them through winter.

The trade-offs: Research published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B revealed that torpor carries significant costs. The study found that mourning doves in torpor (body temperature reduced by 5°C or more) often couldn’t fly when tested, 39% of hypothermic doves failed flight tests that they passed easily after warming up. Birds in torpor are also more vulnerable to predation due to reduced responsiveness.

Why use torpor despite risks? A 2015 comprehensive review in Biological Reviews explains that while torpor creates vulnerability, the energy savings often outweigh the predation risk increase. Birds typically enter torpor only at night in sheltered locations, minimizing predator exposure.

Recent field research: A 2025 study in Behavioral Ecology using wild superb fairy-wrens found that when researchers simulated increased daytime predation risk (via alarm call playback), birds responded by entering deeper and longer torpor bouts that night. The hypothesis: torpor’s energy savings allowed birds to invest more in cautious, energy-costly anti-predator behaviors the following day. This field-based experimental evidence supports theoretical models that torpor increases winter survival by helping resolve the starvation-predation trade-off.

Food Caching: Memory as a Survival Tool

Many winter-resident species rely heavily on cached food supplies hidden during fall abundance.

Extraordinary caching capacity: According to research from Western University on chickadee caching behavior, a single black-capped chickadee can cache up to 80,000 seeds in a season and remember where they all are, and Canada jays cache thousands of food items in bark crevices and among spruce needle clusters for later use.

How caching works: During fall, chickadees, nuthatches, titmice, and jays make repeated trips to feeders, gathering seeds to hide in hundreds or thousands of locations within 150 feet of food sources. Research with chickadees wearing backpack trackers revealed individuals visiting feeders over 200 times daily, stashing prizes under bark, in crevices, and even in human structures like shingles and siding.

The remarkable memory: Chickadees and other cachers possess reversible seasonal changes in their hippocampus, the brain region storing spatial information. This neuroplasticity allows them to remember cache locations with approximately 90% accuracy months later, even under snow cover.

Why caching matters: Cached food provides crucial backup calories during severe weather when foraging becomes impossible. Birds that cache effectively have significantly higher winter survival rates than those without cache strategies.

Roosting Behavior: Communal Warmth and Shelter

Finding or creating shelter dramatically improves overnight survival odds.

Cavity roosting: Black-capped chickadees, eastern bluebirds, and titmice seek cavities or nest boxes for nighttime roosting. According to field observations, temperatures inside tree cavities can be 5-10°F warmer than outside air, and cavities shield birds from wind-chill effects.

Communal roosting: Golden-crowned Kinglets huddle together in groups of 4 or more to share body heat during cold nights. Research shows this behavior can reduce individual energy expenditure by 20-30% compared to roosting alone.

Snow burrowing: Ruffed Grouse and ptarmigan actively burrow into snow for insulation. According to a two-winter field study in Maine published in Living Bird, grouse produce approximately 3.7 fecal pellets per hour while active. One snow den contained about 60 pellets, indicating a grouse may spend 16 hours under snow, including daytime hours during severe weather. Snow insulation can maintain den temperatures 20-40°F warmer than surface air temperature.

Ptarmigan specialization: Willow and Rock Ptarmigan (genus Lagopus, meaning “rabbit foot”) possess feathered feet including toes, unique among birds. These species use feathered feet to dig snow burrows at dusk, tunneling in to spend nights in thermally protected chambers.

Body positioning: Birds tuck beaks and faces under scapular feathers, minimizing heat loss from the head. They also pull one leg up into belly feathers while resting, reducing exposed surface area.

Shivering and Metabolic Heat Production

When other adaptations aren’t enough, birds generate additional body heat through muscle contractions.

How shivering works: Rapid, involuntary muscle contractions generate metabolic heat. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, black-capped chickadees weighing less than half an ounce can maintain 100°F body temperature even when air temperature reaches 0°F through shivering combined with insulation.

Metabolic rate increases: Small birds can boost basic metabolic rate several-fold when temperatures drop. This requires constant food intake, chickadees eat more than 35% of their body weight daily during cold weather, primarily in high-fat foods like seeds and insect larvae.

Daily weight fluctuations: Small birds actually gain weight each day through intensive feeding and lose weight overnight as they burn fat reserves. This daily cycle of fat accumulation and depletion repeats throughout winter.

The movement advantage: Constant foraging activity generates body heat as a byproduct. Birds actively searching for food produce more metabolic heat than if they sat motionless, though this must be balanced against increased exposure to cold and predators.

Limits to heat production: Research shows birds can only increase metabolic heat production so much before it fails to compensate for heat loss. If body temperature begins dropping despite maximum metabolic effort, hypothermia and death risk increase sharply.

Winter Diet and Feeding Strategies

Food choice and foraging behavior shift dramatically in winter to meet increased energy demands.

High-fat food priorities: Winter diets emphasize fat-rich foods providing maximum calories per gram. According to Audubon, fat can account for more than 10% of winter body weight in small birds like chickadees and finches, this stored energy becomes critical during severe weather when foraging is impossible.

Preferred natural foods:

- Seeds and nuts: Acorns, beechnuts, pine seeds, weed seeds provide dense calories

- Berries: Sumac, winterberry, dogwood, Virginia creeper persist through winter

- Insect larvae: Hidden in bark crevices, these protein-rich foods supplement seed diets

- Tree buds: Emergency food when other options are buried

Feeder supplementation: Winter feeding can dramatically improve survival rates. Research shows that reliable feeders providing high-energy foods (sunflower seeds, suet, peanuts) reduce the time birds spend foraging, allowing more time for shelter-seeking and predator avoidance. For guidance on winter bird feeding, including best foods and feeder types, proper supplementation supports winter survival.

Mixed-species foraging flocks: Chickadees, titmice, nuthatches, and kinglets often forage together in winter. These mixed flocks provide multiple benefits: more eyes watching for predators, information sharing about food sources, and cooperative habitat searching. When one bird finds food, others notice and investigate nearby areas.

Altered bill sizes: Fascinating research reveals that some northern bird populations show adaptations for handling cold weather. Bills, legs, and feet tend to be smaller in species wintering in cold zones, scaled down through natural selection to minimize uninsulated surface area and reduce heat loss.

Helping Birds Survive Winter: Research-Based Recommendations

Backyard efforts can meaningfully improve winter survival for resident birds.

Food provision: According to Audubon and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service recommendations:

- Black oil sunflower seeds: High fat content (40%), appeals to most species

- Suet: Animal fat provides dense calories, especially important for woodpeckers, chickadees, nuthatches

- Peanuts: Protein and fat combination supports chickadees, blue jays, woodpeckers

- Nyjer seed: Preferred by goldfinches, siskins, and other small finches

- Quality mixed seed: Avoid cheap mixes heavy in milo and other low-preference fillers

For comprehensive guidance on choosing the right bird feeder for winter conditions, proper equipment helps birds access food efficiently even in harsh weather.

Water is critical: Birds need water year-round for drinking and bathing. Winter bathing maintains feather condition essential for insulation. A heated bird bath prevents freezing, providing vital hydration that otherwise requires energy-intensive snow-melting. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, clean, thawed water is one of the most important winter supplements you can provide.

Shelter provision:

- Roosting boxes: Specially designed boxes provide communal roosting spaces for chickadees, bluebirds, and other cavity users

- Evergreen shrubs: Dense evergreens offer wind protection and roosting sites

- Brush piles: Stacked branches create sheltered spaces for ground-feeding species like sparrows and juncos

- Leave dead trees (snags): When safe, standing dead trees provide cavities for roosting and insect foraging

Native plantings: According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, fruit-bearing native trees and shrubs (sumac, dogwood, holly, Virginia creeper) provide natural winter food. Native plants support more insects, including overwintering larvae birds extract from bark. Understanding native plants for birds helps create year-round habitat supporting winter survival.

Feeder maintenance: Cold-weather diseases spread easily at crowded feeders. Clean feeders every 1-2 weeks with 10% bleach solution, rinse thoroughly, and dry completely before refilling.

Window strike prevention: Shorter days mean dawn and dusk bird activity coincides with poor visibility conditions. Use decals, screens, or UV patterns to prevent window collisions. Understanding how to prevent birds hitting windows reduces winter mortality from this preventable cause.

Species-Specific Winter Survival Strategies

Different species employ distinct winter survival approaches:

Black-capped Chickadees:

- Cache 10,000+ seeds remembering locations via enlarged hippocampus

- Use nocturnal torpor dropping body temperature 7-10°C

- Forage in mixed flocks for safety and efficiency

- Eat 35%+ of body weight daily

Northern Cardinals:

- Don’t migrate; rely on seeds, berries, and feeder supplementation

- Maintain bright red plumage year-round (unlike many species with dull winter plumage)

- Forage on ground and at platform feeders

- Don’t use torpor; rely on efficient food-to-heat conversion

Dark-eyed Juncos:

- Migrate altitudinally (down from mountains) or latitudinally (south from Canada)

- Ground foragers specializing in seeds

- Form large flocks reducing individual predation risk

- Fluff feathers extensively, appearing rotund in cold weather

Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers:

- Extract insect larvae from bark year-round

- Excavate cavities for roosting

- Don’t cache food systematically but exploit persistent larvae

- Visit suet feeders regularly in winter

Canada Jays:

- Extreme cachers storing thousands of food items above snow line

- Breed in late winter (February-March in far north), relying on cached food

- Don’t migrate from boreal/mountain forests despite harsh conditions

- Thick plumage and efficient foraging enable survival in coldest habitats

Winter Mortality: What the Research Shows

Despite remarkable adaptations, winter remains the season of highest mortality for many bird populations.

Research on the severe 1966 Finnish winter found that small resident insectivores suffered the greatest losses, facultative migrants moved south as conditions worsened, and seed-eating residents showed higher survival, according to a Finland winter bird survival study summary.

Research across multiple species confirms winter as a population bottleneck. Factors influencing survival include:

- Body size: Smaller birds lose heat faster, requiring more food per body weight

- Diet flexibility: Species that can switch food types survive better

- Caching ability: Food-storing species show higher survival rates

- Roost site availability: Access to cavities or dense cover improves survival

- Weather severity: Extreme cold combined with ice storms creates highest mortality

Human impact: Window strikes, vehicle collisions, and outdoor cat predation all increase during winter when birds are already stressed. Proper mitigation (keeping cats indoors, preventing window strikes) meaningfully improves survival.

Common Questions About Birds in Winter

Do birds hibernate?

No, birds don’t hibernate in the traditional sense. Only one bird species, the Common Poorwill, enters true hibernation with torpor bouts lasting weeks. However, many species use short-term torpor (hours to overnight), which is fundamentally different from mammalian hibernation.

Why don’t birds freeze on branches?

Countercurrent heat exchange allows feet to cool near freezing without tissue damage, dramatically reducing heat loss while maintaining enough warmth for function.

Can birds freeze to death?

Yes. When birds cannot maintain core body temperature above freezing despite maximum metabolic effort, hypothermia and death result. This typically happens during extended severe weather when food is unavailable.

Do birds get frostbite?

Rarely. Their feet can tolerate near-freezing temperatures without tissue damage. Frostbite occurs only in extreme situations or when feet become wet then freeze.

Why do some birds seem fluffier in winter?

They’re fluffing feathers to trap more insulating air. This behavior, combined with additional winter feathers, maximizes thermal protection.

How do birds know when to migrate?

Photoperiod (day length) triggers hormonal changes initiating migration. Some species also respond to temperature cues or food availability.

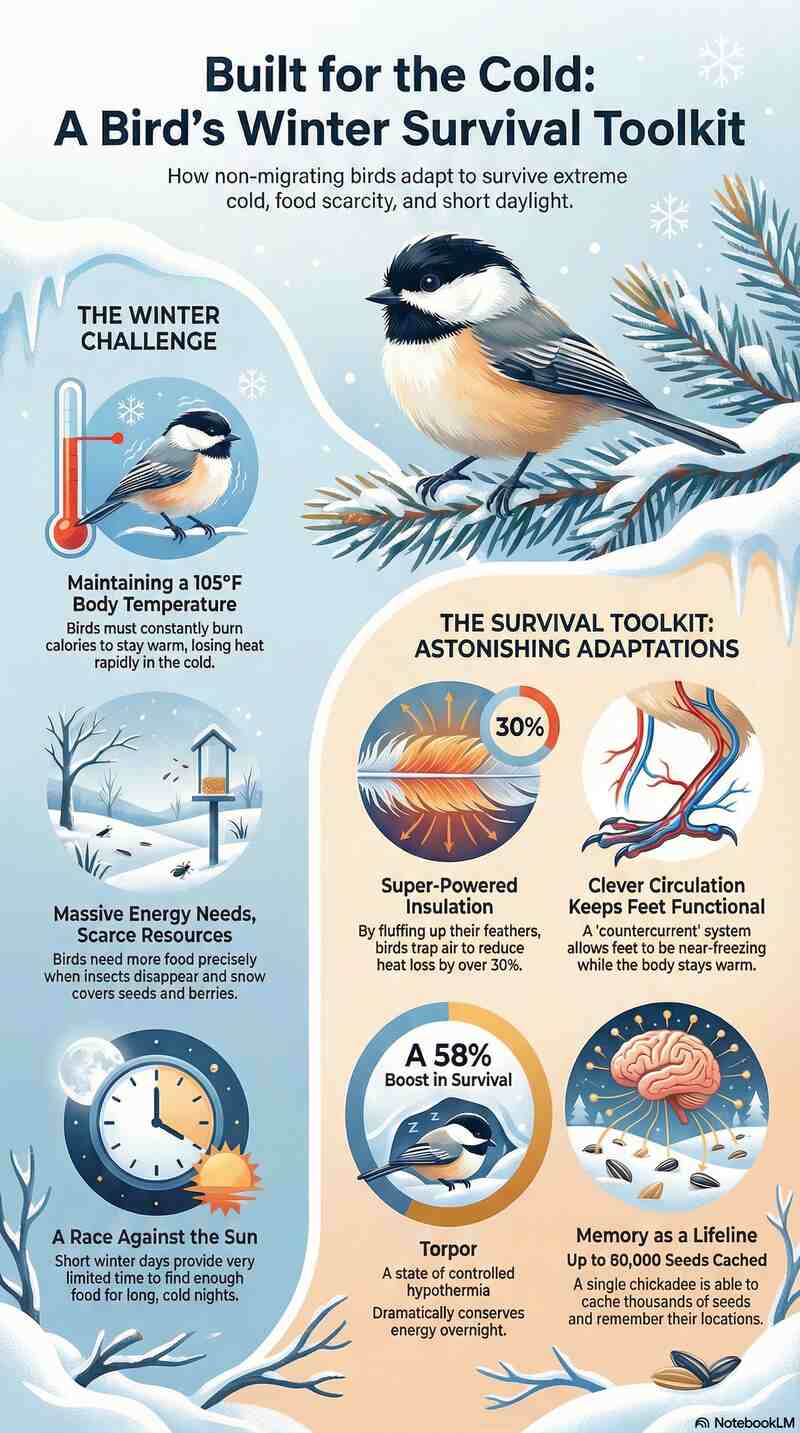

Winter Survival at a Glance

This infographic highlights the key strategies birds use to stay warm, fed, and safe during winter.

Conclusion: Remarkable Resilience Through Evolution

Bird winter survival represents millions of years of evolutionary refinement. The suite of adaptations, from microscopic feather structure to brain plasticity enabling memory of thousands of cache locations, from countercurrent heat exchange to controlled hypothermia, demonstrates nature’s problem-solving at its finest.

Research clearly shows that three strategies working together enable survival:

- Maximizing heat retention: Feather insulation, countercurrent heat exchange, behavioral adaptations (fluffing, roosting, shelter-seeking)

- Maximizing calorie intake: Intensive foraging, high-fat diet, food caching, dietary flexibility

- Minimizing energy expenditure: Torpor, reduced activity during severe weather, communal roosting

Winter isn’t easy, it remains the season of highest mortality. But species that have evolved effective combinations of these strategies not only survive but thrive, returning each spring to breed and repeat the cycle.

For backyard enthusiasts, understanding these adaptations deepens appreciation for the remarkable birds that remain through winter and demonstrates how thoughtful feeding, water provision, and shelter creation can meaningfully support their survival. The chickadee at your feeder in January isn’t just a charming visitor, it’s a testament to evolutionary ingenuity and the astounding capacity of small birds to thrive in conditions that would kill us within hours.